- (https://b-ark.ca/ksKKwg)

I’m riding in the 2025 Enbridge Tour Alberta for Cancer, raising money for the Alberta Cancer Foundation, and have so far raised $2,744, exceeding my $2,500 goal and surpassing my 2024 effort!

Help me by donating here

And remember, by donating you earn a chance to win a pair of hand knitted socks!

Sweet Sweet Sourdough

Well, I did it! Granted, it took two attempts… the first loaf… well, let’s just say it didn’t go terribly well. But the second one turned out very good!

Looks pretty nice, eh? The crumb is a bit on the tight side, but the flavour is nicely sour, and the crust and crumb are chewy, which I kinda like, actually. Should make some mighty fine sandwiches!

Hello World, Meet Ted

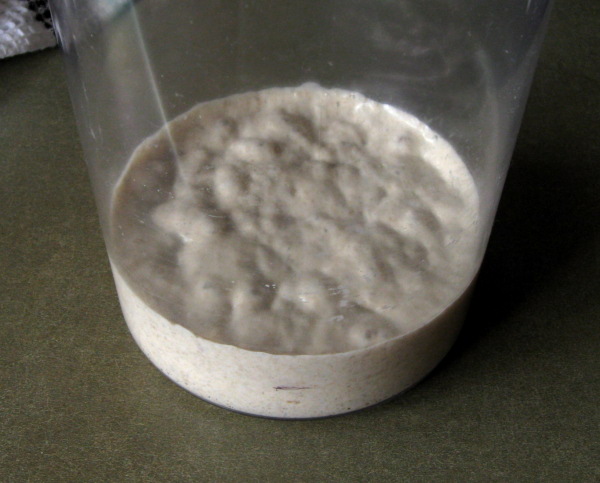

Well, everyone, I’d like to introduce my new friend, Ted:

Yup, my starter lives! And his name is Ted.

For those interested in the gory details, I used the recipe from here. 24 hours in, things looked bubbly. 36 hours in, it was really bubbly. Then the drought of days 3-5… it smelled quite sour, but there was virtually no bubbling to be seen.

At this stage, it felt like things were settling in to a rut, so I made a few adjustments, modifying the feeding as follows:

- Switched from 75%/25% white/rye ratio to 50%/50%.

- Increased the hydration from 100% to 120%, give or take.

Two days later, and you can see the results. It smells lightly sour, yeasty, and it’s doubling in 8 hours. Woo! So tomorrow, it’s sour rye… I hope.

More with the Bread... Again

Well, I took the plunge over the weekend and dropped some hefty dollars to get me a copy of The Bread Baker’s Apprentice, by Peter Reinhart. It is, without a doubt, a fantastic book covering the art and science of bread making, providing excellent pictures, illustrations, and formulae for creating great breads of many different styles, from sandwich to artisnal, yeasted to sourdough.

Of course, with a resource like that at my fingertips, it would be silly of me not to make some bread (despite the fact that I made a pair of sandwich loaves over the weekend (25/65/10 white/WW/rye… yummy!)). So, in anticipation of making some lasagna tonight, I decided to try and execute the Italian bread recipe in the book. The results speak for themselves:

Pretty nice, if I do say so myself! Nice colour, decent oven spring (though not great… the bread formed a bit of a skin during proofing which may have limited spring), reasonable scoring (though not on a proper angle, so no “ears”), and the crumb is just what I was looking for: big, irregular holes, with a nice, soft interior. And flavour-wise it’s deliciously complex, without a hint of yeast. My only complaint is that it’s rather salty, though I think that’s a consequence of the recipe rather than botched execution (the formula has salt at 3.6% by weight… by contrast, French bread has just 1.9% salt).

Up next? Sourdough… eventually. The starter is percolating, and smells distinctly like yogurt, which would be the lactobacillus churning away and lowering the ph. Hopefully today or tomorrow it’ll start smelling more like yeast.

I'm Taking the Plunge

Yup… I said I didn’t have the attention span to maintain a sourdough starter, and, well, I probably don’t.

But I just gotta try it.

As such, I now have a plastic container in my oven, the door propped open with a towel and the light on, containing a 100% hydration blend of organic white and dark rye flours. Here’s hoping it comes to life…