- (https://b-ark.ca/ksKKwg)

I’m riding in the 2025 Enbridge Tour Alberta for Cancer, raising money for the Alberta Cancer Foundation, and have so far raised $2,744, exceeding my $2,500 goal and surpassing my 2024 effort!

Help me by donating here

And remember, by donating you earn a chance to win a pair of hand knitted socks!

- (https://b-ark.ca/mcEOiW)

I haven’t played with linear algebra in a long time, and I won’t pretend to have followed this completely, but this post was very fun! Loved the writing style.

- (https://b-ark.ca/Ow_WSO)

So, to ensure we didn’t bankrupt ourselves during my sabbatical, I realized I needed to get a better handle on our budget and stood up Firefly III. I gotta say, so far, not bad! I particularly love that it has an API with what looks like complete functionality coverage. Just a shame open banking basically doesn’t exist… getting complete transaction data has meant writing Tampermonkey scripts and pulling down data manually. Hard to believe it’s 2023 and that’s still a problem…

- (https://b-ark.ca/uaCgoQ)

Love this piece about AI. It’s a nice, short little primer for the uninitiated.

Tour Alberta for Cancer 2023

Well, the 2023 tour is finally over, and after a couple of days of recovery, a post-ride post!

Well, after a challenging two days in some incredibly intense summer heat, we did it! Team INVIDI completed the 2023 Tour Alberta for Cancer cycling event. And I’m proud to say our team managed to raise another $8,915 dollars for the Alberta Cancer society, all thanks to our many (many!) generous donors who helped the overall campaign reach a whopping $5,560,000 raised, blowing the doors off the $5,000,000 goal that was set for this year.

Continue reading...- (https://b-ark.ca/KMq_WC)

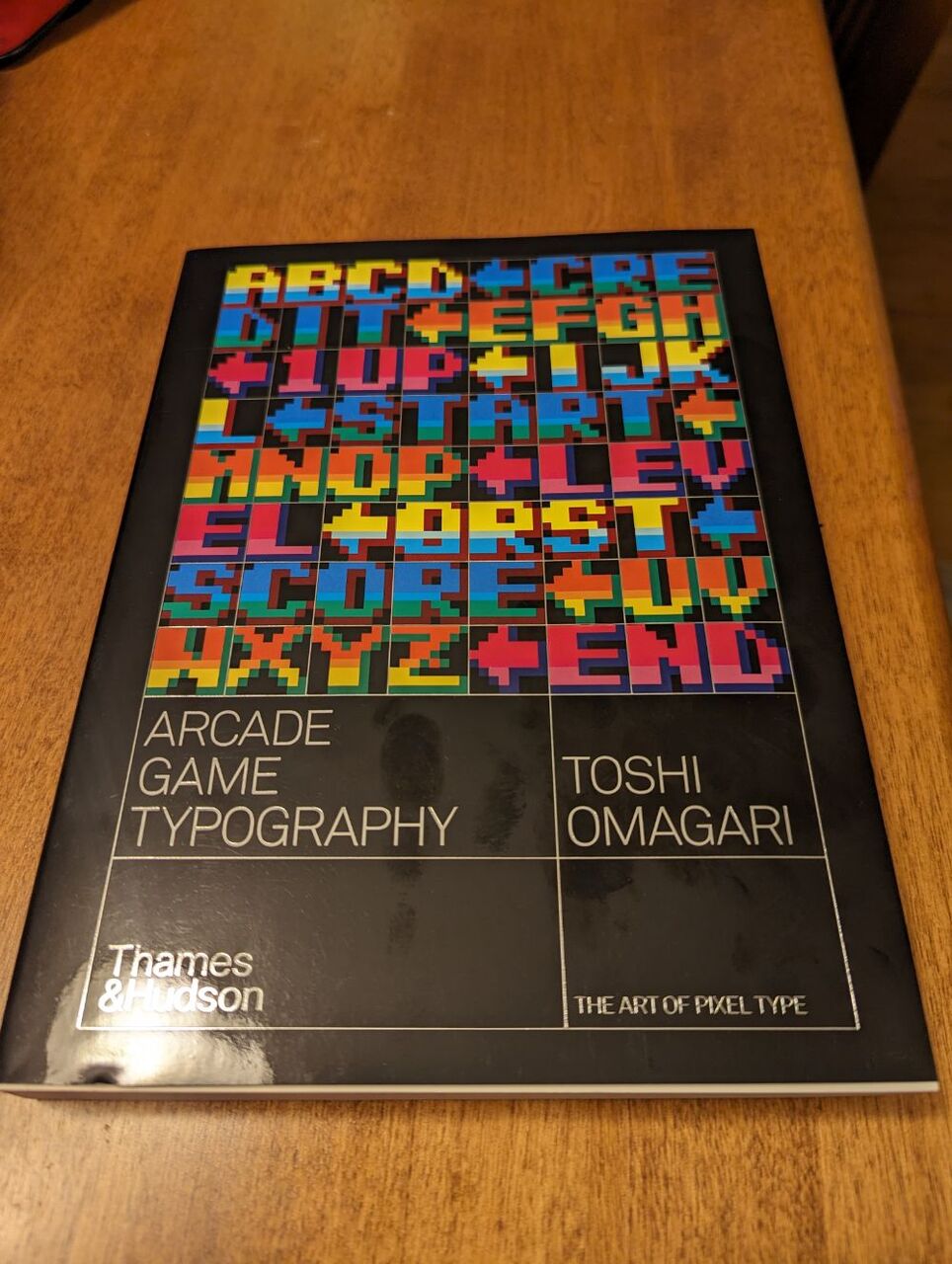

I am irrationally excited about my early birthday gift, Arcade Game Typography by Toshi Omagari. A fascinating and unique take on the history of gaming.

- (https://b-ark.ca/gGaYMu)

A sad day for Evernote users (I haven’t used it any time recently but I know a lot of folks that loved it).

But it’s another good cautionary tale about the dangers of cloud-hosted services. Every company seems invincible until it’s not.

- (https://b-ark.ca/aqMOuk)

An eagle-eyed friend spotted a new arrival in the yard: a newly emerged White Admiral butterfly!

Announcing jekyll-webmention.io 4.0.0

Sabbatical accomplishment! I finally cut version 4.0.0 of this gem for integrating Jekyll with the Webmention.io service, which enables webmentions for static sites.

Well, I must confess when I first agreed to take over maintenance of this plugin I wasn’t prepared for just how burned out I’d gotten at the time, so while I did manage to get 3.3.7 out the door, I have to admit progress was far slower than I would’ve liked.

But, version 4.0.0 is finally done, and I’ve managed to integrate a bunch of changes I had queued up while dealing with a bunch of open issues in the tracker.

Here’s hoping I didn’t break anything horribly (I dogfood the main branch on my own blog but I’m not going to claim that exercises every corner of the codebase, and I’ve not begun the monumental effort to close out issue #29, so automated tests are still very much absent).

With that said, version 4.0.0 of this plugin brings along a couple of major new features, along with some more minor enhancements. While the gem behaviour and associated configuration should be backward compatible with the 3.x series, the changes are significant enough that I felt it best to bump the major version of the plugin so folks are less likely to experience a surprise upgrade.

Continue reading...Ending and Beginning

It’s official, I’m no longer an INVIDI employee. Let the sabbatical begin!

This is a copy of the note I posted to LinkedIn announcing my resignation from INVIDI. Since I didn’t syndicate my last blog post there, you’ll forgive a bit of overlap in the subject matter, but I liked what I wrote and wanted to preserve it on my blog. You know, Own Your Data and all that.

Continue reading...Turning the page

After 21 years in my job at INVIDI I realized I needed a change, and in that moment of change, some space to reflect.

The beginning

Twenty-one years.

For many of the folks I know, twenty-one years is a long time in a career, let alone in a single company.

But the strange thing is that, while on the resume it looks like I’ve had just the one job, in reality I had the great fortune to have experienced a remarkably diverse series of roles, and it seemed like every time I started to get a little antsy, a little bored, in need of a change, INVIDI offered me another opportunity, another challenge, another path to walk.

And it has been quite the journey, though one that has come to its natural end.

Continue reading...