- (https://b-ark.ca/ksKKwg)

I’m riding in the 2025 Enbridge Tour Alberta for Cancer, raising money for the Alberta Cancer Foundation, and have so far raised $2,744, exceeding my $2,500 goal and surpassing my 2024 effort!

Help me by donating here

And remember, by donating you earn a chance to win a pair of hand knitted socks!

- (https://b-ark.ca/AYgsAs)

A little something for the Movember fundraising drive, this is a custom design that I came up with by taking the game graphics and converting them to a pattern.

- (https://b-ark.ca/CSuakk)

Lovely open-work baby blanket I did in the round. I believe this is the first piece I’ve done in this style and it turned out great!

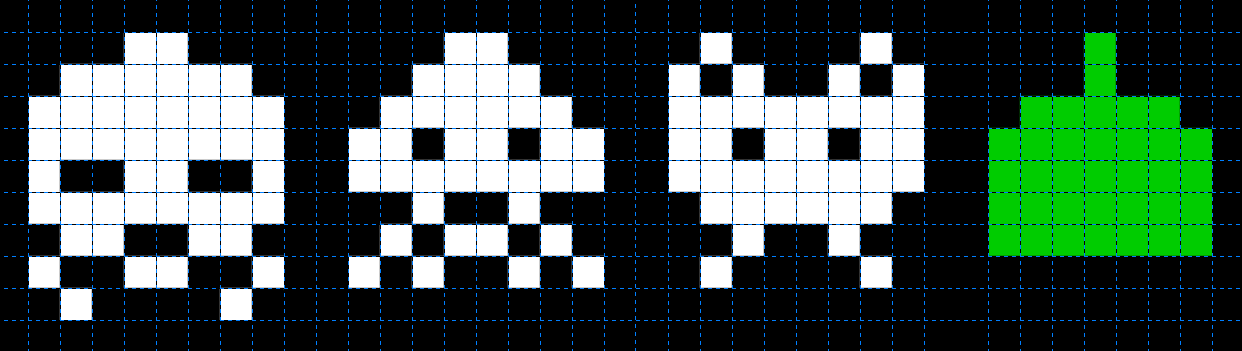

Knitting Space Invaders

I’m working on some secret Movember-related projects, in the hopes of doing a little fundraising through auctioning, and as part of that I needed the sprites for Space Invaders, so I can chart ‘em out. Well, here they are, in case anyone else needs ‘em:

Of course, each of these characters has some variations, as they animate a bit, but these are the basic characters, minus the UFO of course.

Fun with Open Data

A Simple Problem

So, recently I found myself struggling with a very simple problem: I kept missing our darn garbage pickup date. Yeah, sure, the city sends out a little printed schedule, and it usually makes it to my refrigerator, but given that requires I actually pay attention to the silly thing, it doesn’t end up helping me much.

Now, in the past, I’ve solved this problem by manually punching the pickup dates into Google Calendar. This works, but it’s tedious, error prone, and whenever the new schedule comes out, I have to do it all over again. And if it wasn’t clear, I’m lazy. Real lazy. So last time around I simply didn’t get around to doing it.

And so I miss the pickup dates.

Obviously what I really wanted was an iCalendar formatted file that I could just subscribe to in Google Calendar, at which point I could move on with my life. But, alas, to my knowledge no such resource exists.

An Idea Is Formed

Well, I found myself discussing this with my officemate, Steve, and he pointed out that the pickup schedule is, in fact, available online in raw form as part of the City of Edmonton’s Open Data Catalog. The Open Data Catalogue is a remarkable resource. In it you can find a staggering amount of data about the city, provided in a simple, machine-readable form, and browseable online. It’s really very cool, and it feels like a resource just waiting to be tapped.

Anyway, back to the topic at hand, it turns out the pickup schedule is available right in the catalogue, albeit in a fairly raw form. At this point, the answer seemed obvious: write a tool which could consume this data, and produce an iCal file as output. I could then subscribe to the generated calendar, and voila! No more missed garbage days!

Why Can’t Things Be Easy?

Unfortunately, things got a little tricky once we started digging into the data. It turns out that the city is subdivided into a series of zones. Each of these zones then has one or more garbage pickup days, and so one’s individual pickup schedule varies based on your geographic location in the city. As such, the pickup schedule data is organized as a simple table as follows:

Zone Day Date So, now we have a problem: how do we determine the zone and day for a given household?

Well, it turns out the city provides the zone/day data as a geographic overlay, in the form of a KML data file. KML is a rather complex XML dialect which can be used to represent geographic data, and is used in, among other placed, Google Maps, Google Earth, and so forth. But, it’s a standard, and there are standard tools for handling it, so a gold star for the city!

Alright, so now we have the geographic data, we just need to parse that file, and then based on household location, identify the appropriate zone and day, and extract the correct schedule information. This should be easy…

A Solution

The first question was one of language. I knew I needed a few things:

- Access to a decent web framework, so I could quickly slap together a (preferably REST) web service.

- Something to parse the KML data.

- Something to do point-in-polygon tests, so that, given the boundaries of a zone and a household lat/long, I could determine if the household was in that zone.

- A CSV library would be handy (this is the form the schedule data takes).

- A library for generating iCalendar files.

And, in addition, given this was a quick learning project, I figured it’d be nice to choose something I haven’t written much code in. In the end, I settled on Python, and in particular:

- CherryPy - A simple, lightweight web framework with support for REST built in.

- libkml - A KML library with (poorly documented) Python bindings.

- RosettaCode RayCasting Algorithm - Code that implements the standard raycasting point-in-polygon test (I could’ve written this myself, but… why?)

- Python’s standard CSV module.

- vobject - A python library for parsing and generating iCalendar files.

Now, it turns out the hardest bit was in ingesting the KML file. The libkml bindings, while functional, are awful. They aren’t terribly pythonic, they’re horribly documented, and the examples and tests provide no coverage of the API. As a result, I ended up reading a lot of SWIG binding definition files, in order to determine the method calls available in the object model provided. But, eventually, I was able to figure out how to extract both the zone metadata (name, day, etc), and the polygon definitions, and with that, it was fairly easy to write a small library to identify a household zone based on their latitude and longitude.

After that, the rest was really pretty easy: the code determines the user’s zone, downloads the schedule data in CSV form, identifies the rows for that household, and then spits out an iCalendar file containing that schedule data. Voila, done! The service is available here:

http://api.b-ark.ca/garbage/schedule?latitude=&longitude=

Just enter your lat/long, and you should get a valid iCal file back. Nice! And even better, it took me roughly a day to slap the whole thing together.

Getting Fancy

Upon posting about this on Google+, another friend of mine pointed out that it was rather onerous to expect the user to go look up the lat/long of their household in order to use the service. This got me thinking of alternatives… wouldn’t it be great if the user could just provide their address, and the service could do the rest?

Well, happy days, it turns out Google offers a free REST API for geocoding (the technical term for the process of mapping an address to a latitude/longitude pair (or vice versa)). Just hit the service with a street address, and they’ll hand you back geographic data in the form of a JSON or XML document. Nice!

About ten lines of code later (with the help of Python’s minidom module), I had a service which could take an address, get the lat/long automatically, and return the appropriate iCal file. You can hit this version here:

http://api.b-ark.ca/garbage/schedule?address=

Just append your address to the URL, and you could get an iCal file back. Thanks Google!

Update:

BTW, if you want to take a look at the (quite simple) code, you can check it out on github.

Using msysgit in Cygwin

Cygwin sucks. Badly. Particularly on Windows 7, where it’s plagued by the infamous rebaseall bug. As if that weren’t enough cygwin’s git port is terribly slow, and so rather frustrating to use.

Luckily, msysgit offers a fast, well-supported, drop-in replacement version of git for Windows, complete with a nice, clean installer, that fits much better into the Windows ecosystem.

But, alas, it’s not without it’s issues, and so here I’m trying to collect what little tidbits I’m learning as I make the transition.

Using Pageant as your ssh-agent

Set the environment variable GIT_SSH to:

"<path to putty>\plink.exe"And include the quotes! This is related to an issue in git-svn that I’ll mention later.

Merge Tools

You need to grab the entire folder and drop it into

\libexec\git-core if you want any of the mergetools to work. These weren't in my 1.7.7 installed folder, which I suspect is a bug. Later or earlier versions may address this. To use kdiff3 as a mergetool, run:

git config --global mergetool.kdiff3.path <path to kdiff3.exe> git config --global merge.tool kdiff3Git-SVN Gotchas

There’s a bug in git-svn with mergeinfo that can bite you in any version past 1.6.5.7. To get around it, download the 1.6.5.7 tag from here.

Grab git-svn.perl, and replace your copy of git-svn in:

<program files>\Git\libexec\git-coreBut note! This version of git-svn has a bug in it where GIT_SSH has to have quotes around it, lest things go all pear-shaped.

Lingering Issues

If you’re using a cygwin shell (like rxvt), git won’t honour the pager settings, as it can never figure out that it’s running in an interactive terminal. Naturally you can just pipe to your favourite pager by hand, but it’s tricky to get back into that habit.

Mandatory Update

Wow, it’s been a shockingly long time since I’ve posted an update here… seems like I probably should, particularly since I’m now paying for a hosting service to run this damn thing. Might as well actually make it worth my while.

Which brings me to the first major change, largely transparent to anyone strange enough to still be reading this thing, which is that about a month and a half ago, or so, I finally moved my public websites off to Linode. Why Linode? Mainly because, for a modest fee, I get what amounts to a naked Linux box with IPv4 and IPv6 connectivity, upon which I can run basically anything, and so it really just becomes another server in my arsenal, which is rather handy. With it I’m hosting both this blog and my mom’s business website, all more or less highly available, and not victim to the whims of the power company servicing my house.

As a bonus, the upstream on my Linode kicks the ass of the upstream I get at home, so performance should be much quicker for anyone still visiting this place.

Next up, we have another reason why I haven’t posted things here in a while: I’ve got me a Google+ account, and have been moving a lot of my public communications there. Of course, for updates that are directly relevant to my software projects and so forth, I’d rather post them here, so this blog will live on, as rarely updated as it is.

I’ve also been moving more and more of my actual software over to GitHub. The migration is slow, and I’m still struggling to decide which projects I want to move (I’ve got plenty of old Software Projects that I could move, I just can’t decide if it’s worth the trouble), but so far I’ve been damn happy with the results when it comes to NetHackDS, so it makes sense to migrate other projects which make sense (such as the inexplicably popular savsender).

So, there we go, mandatory post complete. Maybe I’ll even author another mandatory post some time in the future. Stay tuned!