Posts in category 'books'

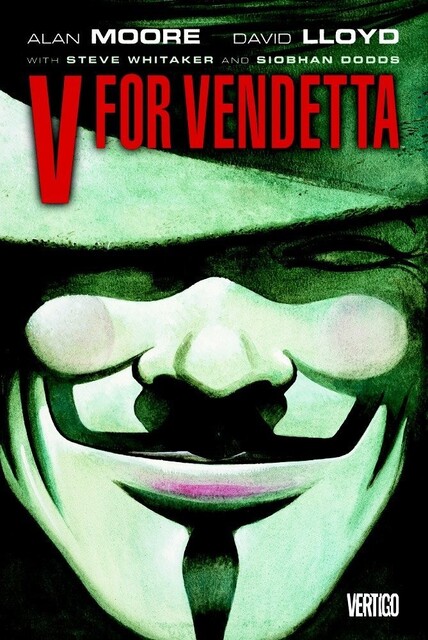

Review: V for Vendetta

Set in a futurist totalitarian England, a country without freedom or faith, a mysterious man in a white porcelain mask strikes back against the oppressive overlords on behalf of the voiceless. Armed with only knives and his wits, V, as he’s called, aims to bring about change in this horrific new world. His only ally? A young woman named Evey Hammond. And she is in for much more than she ever bargained for…

A visionary graphic novel that defines sophisticated storytelling, this powerful tale detailing the loss and fight for individuality has become a cultural touchstone and an enduring allegory for current events. Master storytellers Alan Moore and David Lloyd are at the top of their craft in this terrifying portrait of totalitarianism and resistance.

This paperback edition collects the classic graphic novel, which served as inspiration for the hit 2008 film from Warner Bros.

You can probably guess what this entry is about. Yes, it’s another book review, of a sort. This time, it’s about Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s dystopic graphic novel “V for Vendetta” (Now A Major Motion Picture! (tm)). This whole graphic novel kick I’ve been on was really inspired by the movie adaptation of this book (which is an excellent film, by the way), and so it stands to reason that I would tackle it at some point. My conclusion? It’s good. But I think “Watchmen” is better.

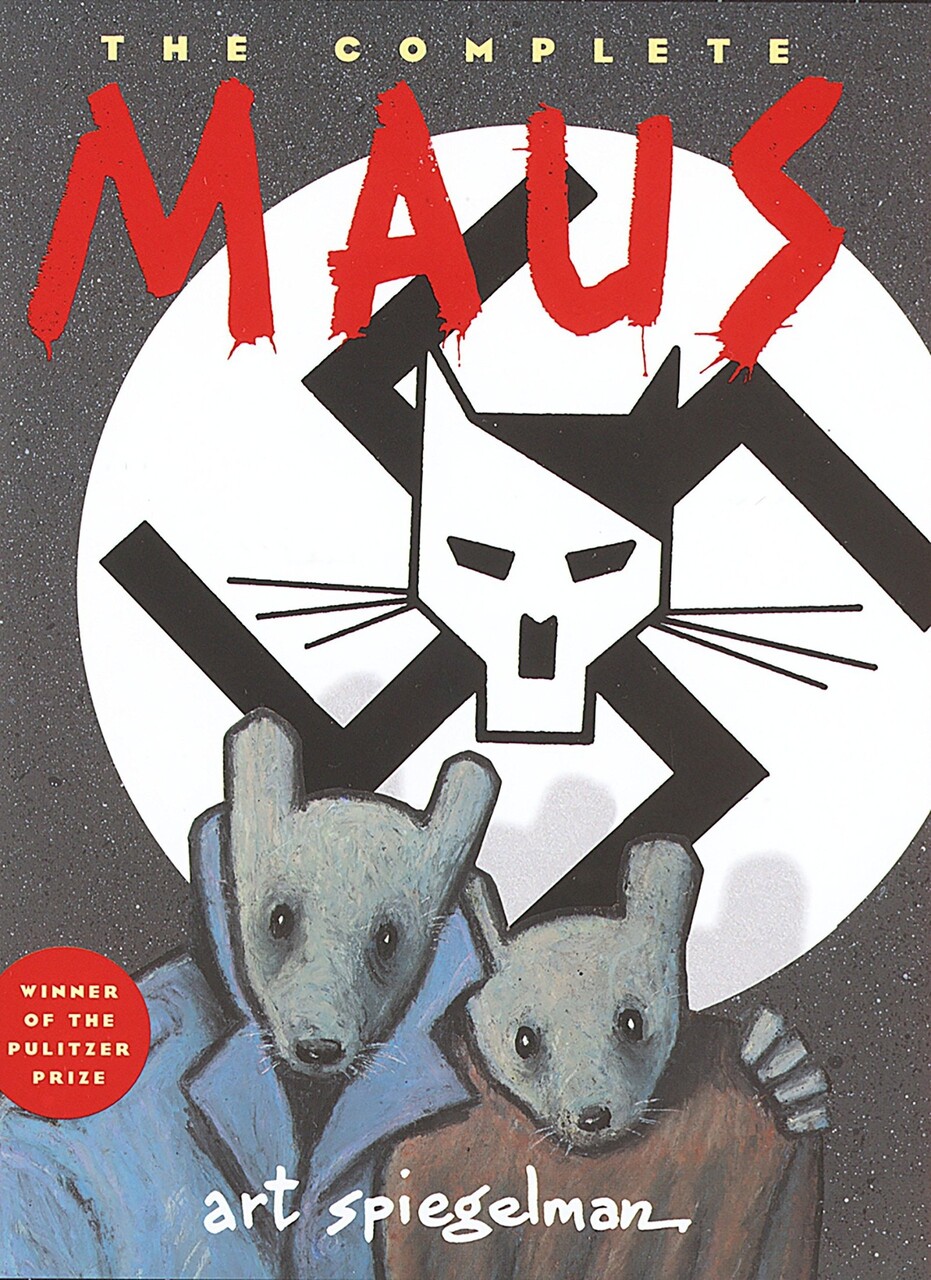

Continue reading...Review: The Complete Maus

The Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus tells the story of Vladek Spiegelman, a Jewish survivor of Hitler’s Europe, and his son, a cartoonist coming to terms with his father’s story. Maus approaches the unspeakable through the diminutive. Its form, the cartoon (the Nazis are cats, the Jews mice), shocks us out of any lingering sense of familiarity and succeeds in “drawing us closer to the bleak heart of the Holocaust” (The New York Times).

Maus is a haunting tale within a tale. Vladek’s harrowing story of survival is woven into the author’s account of his tortured relationship with his aging father. Against the backdrop of guilt brought by survival, they stage a normal life of small arguments and unhappy visits. This astonishing retelling of our century’s grisliest news is a story of survival, not only of Vladek but of the children who survive even the survivors. Maus studies the bloody pawprints of history and tracks its meaning for all of us.

So, as I mentioned in my entry on the graphic novel Watchmen, I chose Maus (and Maus 2) as the next step in my foray into the graphic novel medium. Maus is, first and foremost, the tale of a holocaust survivor. Written by Art Spiegelman, the core narrative surrounds his father, Vladek, and his life in Poland before, during, and shortly after the holocaust. In an unusual twist, the story is told from a sort of metabiographical perspective, in that the reader is presented with a depiction, not only of Vladek’s tale, but also of the author’s experiences as he goes through the process of interviewing his father and writing the book. The result is that we not only learn of Vladek’s experiences surviving the unthinkable, but also the effect these events have on his present day life and the individuals connected to him.

Continue reading...Literary Exploration

In order to reward me for a job well done surviving yet another year on this remarkable little spheroid we call Earth, my lovely wife Lenore came up with the terrific idea of fulfilling a little whim I’ve had recently, that being to go on a minor exploration of the graphic novel medium.

Like many before me, I had always assumed that graphic novels were, in the end, nothing more than extended comic books, replete with your standard super heros and caped crusaders. And while they were certainly entertaining, I would’ve hardly described them as potential sources of real intellectual stimulation. That is, until, I saw the movie adaptation of V_for_Vendetta. “V” demonstrated to me, in dramatic fashion, that graphic novels may also explore complex issues, with interesting, multi-faceted characters. Since then, I’ve been rather curious about the medium and the potential that it holds. Thus, I thought the most natural thing would be to pick up the original “V” and Sin_City graphic novels, so I could enjoy them in their original forms. Unfortunately, a trip to the local book store demonstrated that, following the release of their associated movies, these works have become rather difficult to find. But, not wanting to leave the book store without something, I decided to pick up another work by Alan Moore which I’d heard about: Watchmen.

Now, I should start off by saying I haven’t yet reached the end of this frankly remarkable work. However, to say I’ve been impressed would be an understatement. The only graphic novel to make it on the “Time” list of 100 all-time best novels, “Watchmen” is considered one of the first attempts at a graphic novel as a form of literature. Ironically, “Watchmen” is best described as a superhero story. However, the heros of this story are, with few exceptions, nothing more than regular men and women, with remarkably complex psyches, who’s motivations for donning their costumes and fighting crime are varied and complex. Plotwise, the reader is presented with an intriguingly complex murder mystery, who’s victims are the aforementioned superheros, now retired, forced out of business by a law enacted to quell riots following a police strike protesting the actions of these perceived vigilantes.

If a compelling plot and deep, varied characters aren’t enough, the use of art and dialog in “Watchmen” is wonderful. While not particularly cutting edge, it’s the use of the visuals as a storytelling device that is truly impressive, making it vital for the reader to fully study the panels in order to take in all the details.

So, as I near the end of “Watchmen”, I’ve been trying to decide what to read next. I think I have it narrowed down to three titles:

“Maus”, a work for which it’s author, Art Spiegelman, won a Pulitzer, presents the story of Artie and his father’s experiences surviving the holocaust. “Blankets”, a memoir by Craig Thompson, explores the issues of an adolescent growing up in a fundamentalist Christian home. And lastly, we have “From Hell”, another work authored by Alan Moore, which presents a conspiracy theory involving Jack the Ripper. Intrigued? Perhaps you should check out a graphic novel… you never know, you might like it.

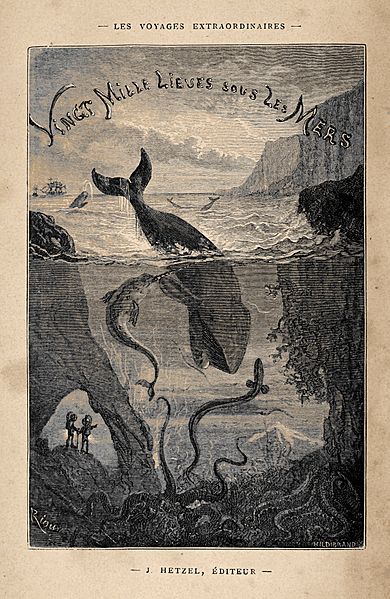

Review: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas: A World Tour Underwater is a classic science fiction adventure novel by French writer Jules Verne; it was first published in 1870. The novel was originally serialized from March 1869 through June 1870 in Pierre-Jules Hetzel's periodical, the Magasin d'éducation et de récréation.

Well, last night I finally finished reading 20000 Leagues Under The Sea by Jules Verne (author of The Journey to the Center of the Earth and Around the World in 80 Days, among many others). This book, depicted in the 1954 Disney film of the same name, details the adventures of Professor Pierre Arronax, an oceanographer, and his companions Ned Land, a Canadian whaler and Conseil, the professor’s manservant, as they travel aboard the Nautilus, an advanced submarine designed and built by the infamous Captain Nemo.

In terms of historical context, Jules Verne is considered, along with a number of his contemporaries, as early examples of science fiction authors. Often compared with H.G. Wells (The Time Machine, The War of the Worlds), who used science fiction as a medium for making points about society, Verne focused on providing depictions of realistic technology that was logically extrapolated from that of the present day, and used that technology as a basis for more adventure-oriented works.

20000 Leagues most certainly fits this mold. The Nautilus and it’s attendant technology are carefully detailed by Verne, who attempts to very clearly describe the workings of the ship and it’s scientific underpinnings. This ship then becomes the vehicle (if you’ll pardon the pun) for an adventure story which carries the crew to nearly all points of the compass, from the Pacific to the Atlantic, Antartica to the North Sea, and into the deepest parts of the ocean. Along the way, the reader is introduced to countless species, running the gamut from coral to fish to whales, as well as various birds and semi-aquatic mammals.

Continue reading...