Taking Control of Chat

Documenting my absurd journey to bridging an IRC client to a bunch of messaging services. Totally nuts and totally worth it.

IRC, or Internet Relay Chat, is unquestionably the progenitor of modern online chat systems.1 IRC preceded instant messaging platforms like ICQ or AOL Instant Messenger, and in doing so connected people in real-time in a way that would lay the groundwork, not for just those instant messaging platforms that would follow, but for modern social media platforms as we know them today. And today, while certainly diminished, IRC still plays an important role in connected communities of people, particularly in the IT space.

But IRC isn’t without its flaws, and those flaws created openings for many competitors:

- Chatting is ephemeral. If you’re not connected there’s no way to receive messages that were sent while you were away.

- Text-based. No images or giphy animations here, and file sharing is direct, client-to-client only.

- The mobile story in general, and notifications in particular, are weak.

Now, the IRC community has worked hard to address the first problem with bouncers and changes to the IRC protocol (I’ll dig into this later).

Issue two… well, bluntly, I actually view that as a benefit rather than a drawback, but obviously that’s a matter of personal taste.

As for issue three, it’s still true that the mobile story isn’t great, though there is slow steady progress (Android now boasts a few pretty decent mobile IRC clients).

But IRC also has some enormous benefits:

- It’s open and federated. Running a server yourself is trivial.

- Clients are heavily customizable for power users.

- It’s fast and lightweight.

And these various other products (like Slack, Signal, etc) have some mirror image drawbacks:

- Closed walled gardens.

- Zero ability to customize.

- Heavy, memory- and CPU-intensive clients.

And then there is the fragmentation. My god the fragmentation. Every app is its own beast, with its own UX quirks, performance issues, bugs, and so on. Even the way they issue notifications varies from product to product. And some (I’m looking at you, Whatsapp) don’t offer a desktop client product at all.

I spend every day working with these messaging products, and I wanted to find out: Is there some way I could use an IRC client of my choice to interact with these various walled gardens (recognizing that, yes, that would come with some loss of functionality)?2

Well, with a lot of hacking and elbow grease, I can definitely say the answer is yes! Though… this is, as is the case with many of my projects these days, probably not for the faint of heart…

Let’s talk about bridges

The idea of a messaging bridge is as follows:

You can think of the bridge as a kind of adapter. To the IRC client it presents what looks like an IRC server, where the users and channels correspond to users, group chats, and so on, on the private messaging service.

In contrast, the service sees what looks like a normal client, with the user conversing with individuals and groups as usual.

The bridge provides the translation layer so that this all works smoothly.

Okay, maybe not perfectly smoothly! Bridges like this have to adapt messaging platforms with potentially disparate feature sets, and that doesn’t always work cleanly. For example, Slack has the concept of direct messages, multi-party direct messages (aka groups), and channels. IRC, by contrast, only provides direct messages and channels. So any Slack bridge must map group chats to channels, which can result in some pretty odd looking channel names.

Similarly, tricky concepts like emojis, reactions, message threading, image and file attachments, and so on, don’t easily map to IRC. The result might be lost functionality or somewhat clunky workarounds.

And there’s still the problem of IRC chats being ephemeral. That is, if a client isn’t connected to the bridge, any messages from the service are lost (though, as we’ll see later, there’s an app for that).

So why, you ask, would you ever bother?

The power user dilemma

I admit it: I’m a control freak.

I want my computers to do my bidding. I want to have a clear understanding of how they function, and I want to be able to change it if I want.

I really don’t want choices forced upon me. The minute software leaves me with the sense I’m out of control or I’m having a choice forced upon me, the more likely I am to resist.

You can see that in my choice of operating system (Linux), my choice of browser (Firefox), my choice of blog platform (Jekyll)… the list goes on. Given the choice between a challenging, complex system that I can build and control, or a simple system where I have none, I’ll pick the former every time.

Modern messaging systems are terrible for anyone like me. Each platform has its own apps and desktop software (or, in some cases, a webapp), all of which are uniformly bloated while offering absolutely no avenues for customization, automation, or integration. Even something as basic as control over notifications is crude at best.

In this respect the world of IRC is the polar opposite. The protocol itself is an open standard. IRC clients are numerous with flavours that appeal to a wide range of tastes. Client flexibility, customization, and extension is practically a genre trope. Power tools, like bouncers, bots, and so on, are a dime a dozen.

In short, this is my jam.

A bit about bouncers

Recall off the top that one of the downsides of IRC that I mentioned is that chatting is ephemeral. This means that, if I log off of an IRC server, and the conversation goes on, unless a log is kept, there’s simply no way for me to ever find out what was discussed. This applies to both direct messages and conversations on an IRC channel.

This is a huge downside! We can’t all be available, with an IM client at the ready, at all times. Clearly this requires a solution if IRC is to be a viable messaging option.

Fortunately, the IRC world invented the concept of the bouncer. The bouncer fits in as follows (and this will look familiar):

The idea of a bouncer is that you stand one up on some server somewhere that’s online and available 24/7. To the IRC server, the bouncer is an IRC client. To the IRC client, the bouncer is an IRC server.

If the IRC client issues a request to join a channel, the bouncer relays that request to the server and joins the channel. When messages flow back and forth, the bouncer passes them along.

But the key is what happens when the client disconnects: The bouncer keeps running and stays connect to the server, so that to the server, nothing has happened.

While the client is disconnected, the bouncer stores all those messages so that, when the client reconnects, it can request the message backlog and replay it to the user.

In short, this solves the problem of chatting being ephemeral on IRC.

Now, it’s not a perfect solution. A bouncer will have a limited capacity to store messages. It may lack the types of search functions that a product like Slack might offer. And it does require an always-on server to host it.

But if you can live with those limitations, this can work great! And critically, a bouncer plays together very nicely with IRC bridges…

Putting the pieces together

Rather than describing the idea, let’s just show it, shall we?

Get it? If we can set up a bunch of bridges and connect them to a single bouncer, we can use a single, flexible, customizable IRC client to talk to all of these messaging services!

Wouldn’t that be nice!

Aside from IRC itself, there are three major messaging platforms I find myself using:

- Slack

- Signal

The question, then, is: are there IRC bridges available for each of these platforms? And the answer is “yes”, but it is a qualified, complex “yes”. Some of these bridges are extremely well done (Slack), others are in development and a bit early but have an active maintainer (Signal), and yet others seem sorta in limbo (Whatsapp).

Slack

By far one of the best-supported bridges I came across, irslackd is an exceptional project. The maintainer is extremely responsive. The supported feature set is excellent. The codebase is simple and accessible. And setup is pretty straight forward.

The only really tricky bit is pulling your Slack token out of your web browser, but after a minor misstep (Hexchat has a password length limit that was clipping the token…) I got it working flawlessly.

In addition, I’ve already worked with developer to add a new feature (starting group chats with the “@slack chat” command), and I’ll probably add some more customizations in the future.

Honestly, if all the bridges were this easy, this wouldn’t have been nearly as much fun.

Signal

Before I begin, a critical caveat: By bridging Signal to IRC as I’m about to describe below, you are absolutely taking your security, and the security of those you correspond with, into your own hands. If security is important to you, you must take a lot of precautions–and I’m no expert, so this should not be seen as authoritative. At minimum, you must ensure all of your connections are TLS encrypted and server authentication uses very strong passwords. Be aware that your IRC client, bouncer, and even your system logs may end up containing plain text copies of messages or other sensitive data. Any breaches of your infrastructure may place your communications at risk. In short: security is incredibly hard, and by doing this, you are taking it into your own hands.

Alright, with that out of the way…

Oddly, despite providing a supported library that implements the Signal protocol, there have not to date been a lot of implementations of new, Signal-compatible clients or bridges. After doing a bit of a survey, the best option I found appears to be libpurple-signald, and it warrants a bit of an explanation.

First, let’s talk about libpurple. Purple is basically a chat protocol API that forms the core of Pidgin, a multi-protocol instant messaging client. A library that implements the libpurple API can be dropped into Pidgin, thereby extending it to support additional protocols.

Next we have signald. Signald is a standalone daemon that uses the Signal Java library to talk the Signal protocol on one side, and exposes a nice, simple, JSON protocol on the other side. In essence, it serves as an abstraction layer over the Signal protocol and hides a bunch of the complexity of supporting the thing.

And then, finally, we get to libpurple-signald. As should be implied by the name, libpurple-signald is a library that conforms to the Purple ABI and talks to signald on the other side. With it you can use Pidgin as a Slack client, communicating through signald! Neat!

But why is that relevant to me? After all, I have no intention of using Pidgin…

Okay, here’s the last part: Bitlbee. Bitlbee is a multi-protocol IRC bridge that supports libpurple libraries as protocol plugins! So here’s what we have:

Yes. This is a bit complicated.3 But it works!

I will note, libpurple-signald is the one project where I’ve done the most active work to enhance the project4.

First, the project didn’t have proper group chat support, so I’ve contributed an implementation of Signal group chat support that aligns well with the way libpurple functions, along with a significant refactoring to break the project up. These changes have been working extremely well for me.

Second, I added a new method for attachment handling. By default, libpurple-signald uses a method for inlining images into Pidgin conversations that Bitlbee doesn’t support (what with IRC being text-based, that shouldn’t be a surprise). Stealing an idea from other bridges, I added a new mode where the attachments are saved to a directory that can be offered up by a web server. The library will then dump an appropriate URL into the conversation so you can click it to see the attachment. This, too, has been working very well for me.

Finally, signald itself has been a little unstable, so I’ve been working with the author and others to get some bug fixes in place, and so far it’s working pretty well for me!

Finding a Whatsapp bridge was easily the most fraught part of this experiment, and honestly, I expect it to be the least stable in the long term. Where Slack has a well-supported API and Signal provides a Java library, Whatsapp bridges operate purely on the power of reverse engineering and a lot of hackery. Yeah, there are attempts at libraries like whatsapp-web-reveng but you’re always on pretty shaky ground.

But that doesn’t stop people from trying, and the bridge I chose is sms-irc, which, I know, based on its name wouldn’t appear to have anything to do with Whatsapp. Oddly, it’s a bridge that provides two functions: SMS support for computers with a 3G modem, and… Whatsapp support. Go figure.

Even more oddly, sms-irc itself doesn’t implement an IRC server. Rather, it integrates with InspIRCd, which is what implements the actual IRC protocol.

Now, deploying sms-irc did not turn out as simple as I would’ve hoped. When I first set up sms-irc as a docker container, it immediately didn’t work, and a bit of digging and guesswork led me to conclude that the Whatsapp Web client version was newer than the one reported by the bridge.

Digging a little deeper, I discovered that sms-irc is built on whatsappweb-rs, and that the library appeared to have been recently updated to bump the client version. Great! I guess I just needed to build from source!

Oh, except the library has recently been updated in a way that breaks the API, and sms-irc has not been updated to match. To deal with this, sms-irc references a branch of whatsappweb-rs that pre-dates that change, but a) the branch doesn’t exist anymore, and b) even if it did, it’d also pre-date the version bump.

What is a hacker to do?

Obviously pull down the whatsappweb-rs git repository, revert the API change while keeping the version bump in place, and then rebuild sms-irc using my custom library.

And remarkably… it… works! Very well, in fact. Direct messages, group messaging, and even attachments (which also get served up by a self-hosted web server that I run) all work perfectly. Nice!

I genuinely have no idea how long this is going to last, but eh, I’m pretty happy with it for now!

What about the bouncer and client?

Oh yeah, I suppose I should mention, I ended up choosing ZNC as my bouncer, Weechat as my desktop IRC client, and Revolution IRC as my mobile client.

ZNC was incredibly easy to set up and manage, and I’ve added a few modules to the mix:

- fail2ban

- Block repeated login failures after 5 attempts.

- savebuff

- Persists the channel buffers in an encrypted store on disk.

- clientbuffer

- Ensures each client gets its own replay buffer.

Weechat, by contrast, has a bit of a learning curve, but I gotta tell ya, I’m extremely happy with it. I’ve re-styled the interface to use a bunch of unicode characters and so forth for clean lines and iconography. I’ve also added a bunch of scripts to the mix:

- atcomplete

- Performs autocompletes for nicknames when they proceed with an

@character. Very useful for Slack! - highmon

- Captures highlights in a buffer that you can reference.

- autosort

- Sorts the buffer list according rules you set. I’ve set this to ensure channels appear under their server, and that Slack multi-party chats appear after the regular channels but before DMs.

- buffer_autoset

- Automatically applies settings to buffers based on rules you specify. I’ve used this to set highlight rules for Slack multi-party chats, for example.

- emoji_aliases

- Converts emoji short-codes to their Unicode equivalents, which is handy for Slack.

- go

- Quick buffer navigation.

- grep

- Search through chat logs.

- notify

- Provide OS notifications on highlights so I know when someone is trying to get my attention!

- urlgrab

- Easily open URLs posted to channels. Especially useful for all those image attachments and so forth.

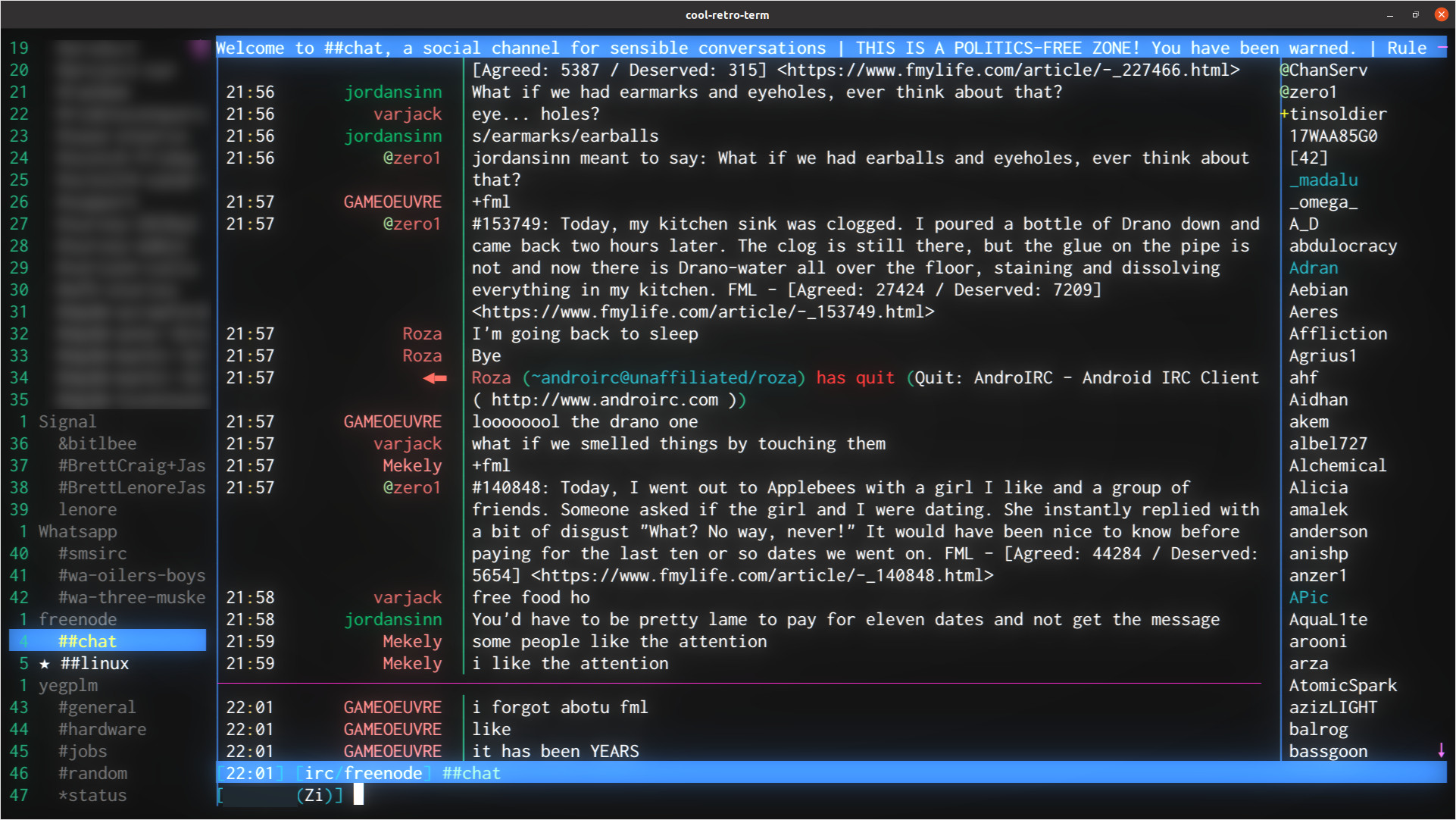

Combined with cool-retro-term, it looks like a million bucks and works great!

Finally, Revolution IRC is… eh, good enough. Again, the IRC story on mobile is just okay. I’ve definitely not ditched the dedicated chat apps on my phone. Yet.

The result

The final monstrosity:

ZNC and all the bridges are running on an Ubuntu 20.04 image on my Intel NUC, and so all that traffic sits within that node. Meanwhile, all connectivity between the clients and ZNC is TLS encrypted, with access controlled with a very strong server password.

And, of course, an obligatory screenshot:

The verdict

I fully accept that this is completely insane. But you know what’s even more insane? It a) works more or less perfectly, and b) I absolutely love it.

Weechat has been a delight to use, with an insanely high level of configurability and control. I forgot just how much I love using a lightweight, scriptable, terminal-based chat client. It really is enormously freeing.

And having all my messaging activity flowing through a single interface has actually made me more likely to communicate. Whatsapp, in particular, was always a chore and now it’s just another server alongside a bunch of others in my IRC client.

I’ve even dipped my toe back into IRC (hence Freenode), which has proven to be a surprisingly enjoyable throwback!

Overall, this has been an incredibly satisfying project. The rough edges gave me fun projects to work on, and the payoff has definitely been worth the effort.

-

Heck, Slack, which has taken the world by storm, is heavily influenced by IRC, including using ‘#’ characters for prefixing channel names, and using ‘/’ as the leading character for issuing commands. ↩

-

Credit where credit is due, it was Matrix that first gave me this idea, where bridges are extremely common. ↩

-

The author of libpurple-signald is actually looking to build a straight libpurple library that wraps the Signal java library, but it’s still very much in the experimental phase. ↩

-

As of this writing these changes haven’t been merged upstream, so for now you can find my changes on Github in my own fork of the repository. ↩

Likes

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{{ webmention.content }}

{% endfor %}

No bookmarks were found.

{% endif %}Likes

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{% if webmention.author %} {% endif %}

{% endfor %}

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{{ webmention.content }}

{% endfor %}

No links were found.

{% endif %}Replies

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{% if webmention.author %} {% endif %} {% if webmention.content %} {{ webmention.content }} {% else %} {{ webmention.title }} {% endif %}

{% endfor %}

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

- {% endfor %}

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

- {% endfor %}

No reposts were found.

{% endif %}-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

- {% endfor %}

No RSVPs were found.

{% endif %}-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{% if webmention.author %} {% endif %} {% if webmention.content %} {{ webmention.content }} {% else %} {{ webmention.title }} {% endif %}

{% endfor %}

No webmentions were found.

{% endif %}