Handwired Alpha - Assembly

Assembly of Alpha occurred over three furious sessions of soldering, followed by a week-long break (which I will explain later), and then final assembly.

Session 1: Sockets and diodes

Normally, the first step of assembling a keyboard is to mount the switches to the plate, and then solder diodes to the switches. The beauty of using Kailh hotswap sockets is that, instead, I could just solder the diodes to the sockets first! This made the job a lot more pleasant, since I could wrap the diode around the socket, put the whole thing on a helping hand, solder, then mount the socket on the target switch.

Initially I tried slipping the diode lead through the break in the hotswap socket lead, only to discover that doing so spread the socket contacts and cause it to no longer hold tight to the switch! Realizing this, I altered my plan and instead wrapped the diode lead around the socket lead, then soldered the whole thing together. You can see the result here:

Critically, it was important, for the first diode, to place the socket on the switch, verify which side would be connected to the row, and then use that to determine on which side the anode would be placed. After that I just had to be consistent.

I also made sure to bend the opposite lead (in the opposite direction!) to support later soldering the magnet wire to diodes. All leads were bent using a lead bending tool to ensure consistency in the bends. Below you can see the completed work product:

Throughout this work I made sure to use a multimeter to test every diode before soldering, and every socket after soldering. I also tested every switch though, since I was using hotswap sockets, this was a lot less important! This validated that the socket, switch, and diode were working and arranged correctly.

And good thing, too! I soldered one diode on backwards…

Session 2a: Matrix design and pin assignment

The keyboard matrix ties the switches into a set of rows and columns, which are then soldered to pins on the controller. This requires the design of keyboard matrix itself (since you need to decide how the switches will be assigned to the matrix positions), along with a pin assignment (to determine which pins on the controller will represent each row and column).

Fortunately, there is an online QMK Firmware Designer that includes an interactive tool for both of these tasks, with the added bonus that it will attempt to automatically build a matrix (which I then heavily altered), and can generate a QMK source bundle that is configured with the specified design!

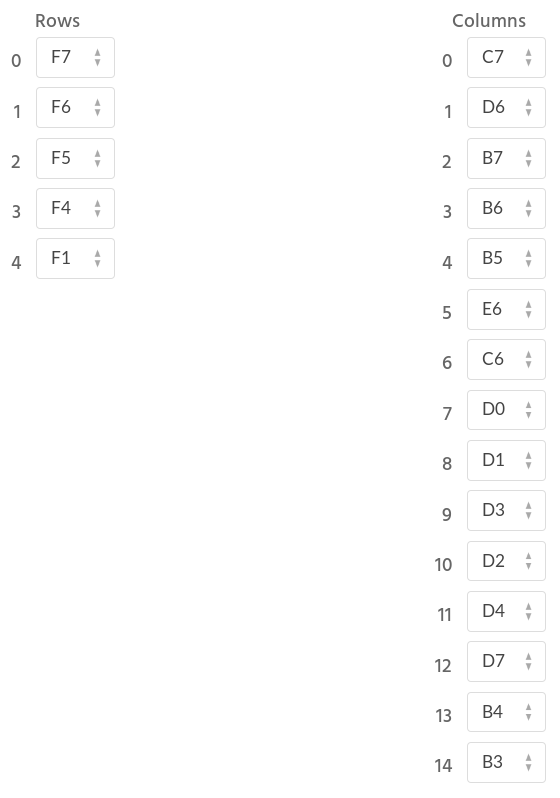

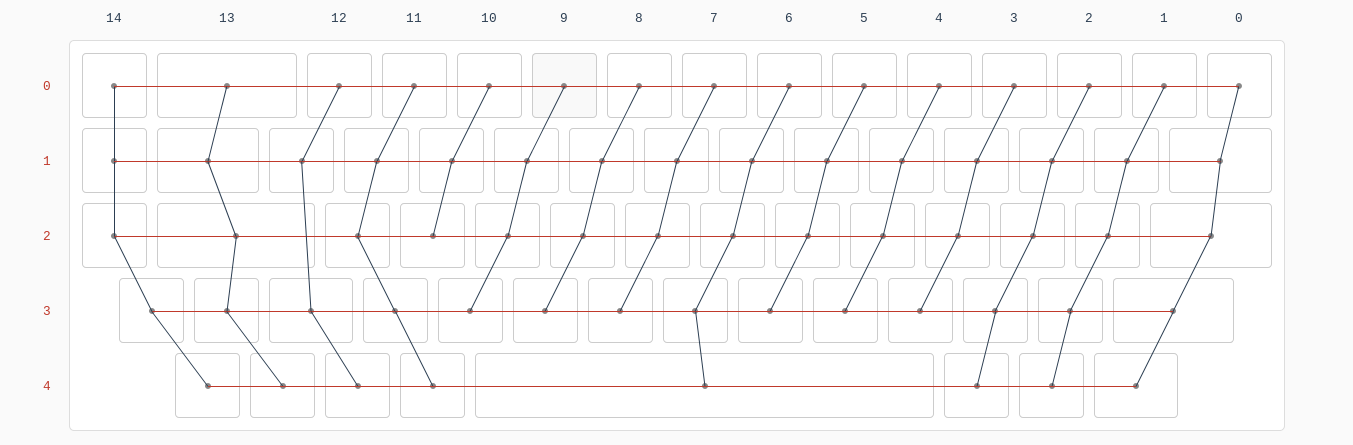

Thus, armed with the Itsy Bitsy AVR pinout diagram, I was able to produce the following matrix design:

Assigned to the pins as follows:

A huge shout-out to the authors of this firmware builder, as it made it infinitely easier to get my matrix layout just right!

Session 2b: Controller pins

As I mentioned previously, rather than soldering wires directly to the Itsy Bitsy or even to a set of header pins, I decided to make use of a set of board mating sockets. As a result, the very first thing I had to do was solder sockets to the pins assigned to my matrix. You can see the arrangement here:

At this point I could’ve chosen to solder the switches together into a matrix, and then solder the matrix to the controller. However, I was concerned that, if I did that, I’d have trouble cleanly routing the wires back to the controller.

As a result, I decided to work the other way, attaching the wires to the controller, and then soldering the switches into a matrix using those wires.

This worked incredibly well!

To attach the wires to the controller, I chose to solder wires to the associated pins I would be using with those sockets. And here is where I made a minor mistake: Thinking it would be safer, I decided to start soldering the wires to the pins without first mounting the pins in the sockets (similar to how I attached the diodes to the sockets). As a consequence, the pin header warped due to the heat of the soldering iron!

I discovered this warping part way through the soldering job and realized I needed to install the pins in the sockets, and then solder (as the socket would keep the pins straight). Fortunately, with a bit of force, I was able to get the socket onto the board and finish the work. Lesson learned!

The soldering itself was done by scraping the enamel off the wire with a knife to form a lead, bending the lead into a hook around a spare set of pins, trimming off the extra length, and then attaching the lead to the pin.

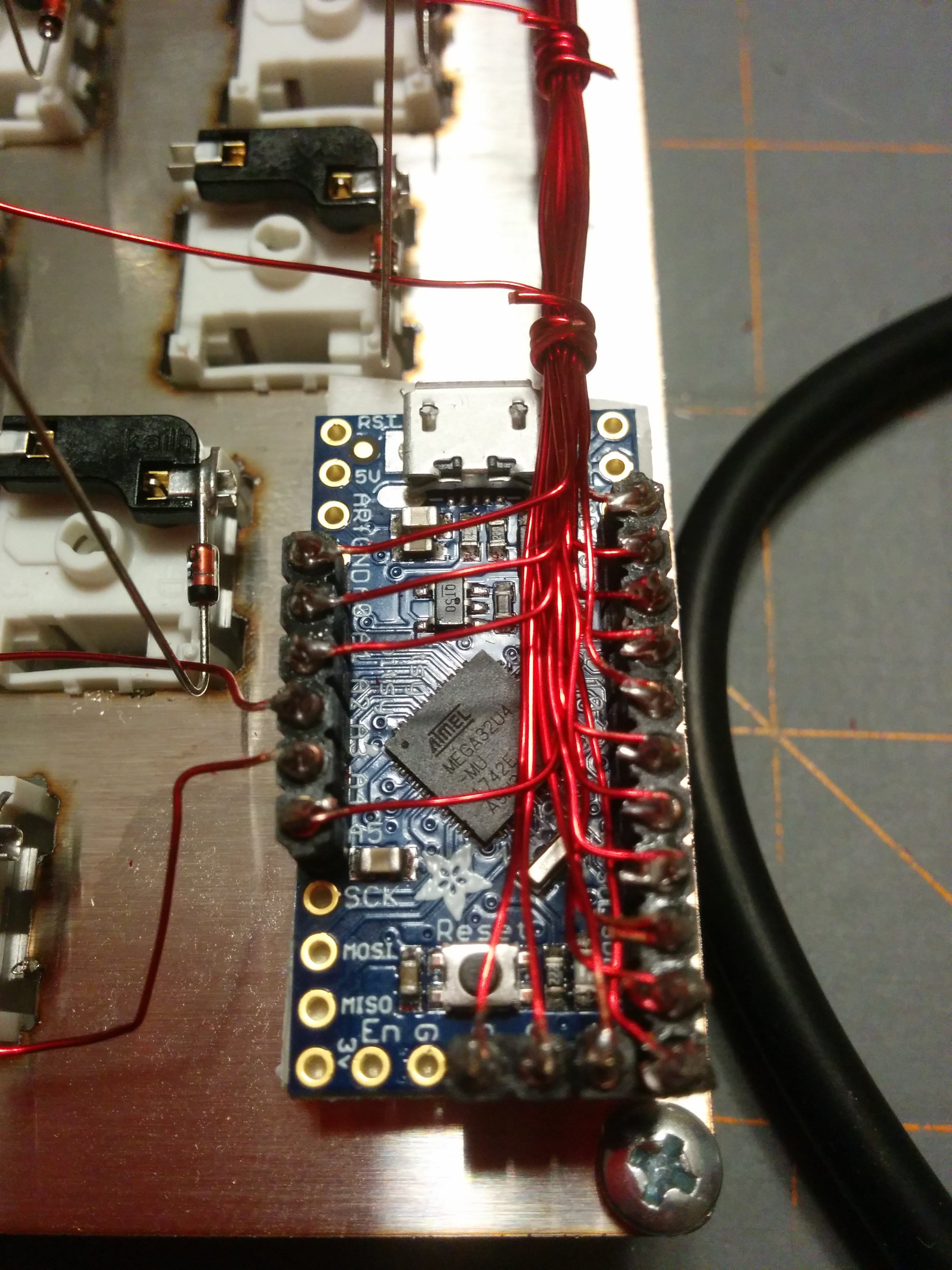

The final work product can be seen here (this photo was taken after I began assembling the matrix, but you can see how the wires are attached and routed):

And please, no messages about my filthy soldering job, here… I’m just amazed there aren’t any shorts!

You’ll note that two of the wires are facing away while the rest of the wires are facing inward and routed so they can be bundled together. As I completed the column wires, I tested laying the controller in the case to see how the wires would best be routed. In this way I noted that two of the rows would best be routed as shown in the image, while the rest would be routed together.

Throughout the work, I made sure to test every wire to verify I’d scraped off sufficient enamel, tested every joint after soldering, and tested adjacent pins to ensure no shorts. And, of course, I tested the controller after assembly to ensure I hadn’t fried the thing somewhere along the way…

I will say, this was hands down the most tedious part of the job. Due to the delicacy of the work I really had to take my time. Scraping the enamel off the wires was time consuming and error prone. Forming the leads required a fine touch. Trimming the excess had to be done extremely carefully. Then, as the work progressed, the wires became increasingly irritating to manage. I easily spent the same amount of time soldering the 20-ish pins as I did assembling the 60-ish sockets!

Session 3a: Matrix construction

With the controller connected I could move on to the main event: assembling the matrix itself!

To keep the work as clean as possible, I used 22 AWG magnet wire to bundle the wires together (in hindsight I could’ve used zip ties, but I liked the look of the final result!) In each spot where I needed to peel away a wire, I wrapped the bundle, which kept everything neat and tidy.

I began by first mounting the controller to the case itself. How? Using 3M Command adhesive strips!

This versatile little product provides two velcro-style strips, which mate to one another, combined with an incredibly strong adhesive. Using this product I could mount the controller to the plate while still allowing me to easily remove or slightly reposition it.

Handy!

It was also no accident that the key layout I designed made for ample space to mount the controller to the plate, as normally it would have to be positioned under the spacebar, or somewhere beneath the switches themselves.

With the controller in place, I could assemble the switches into rows.

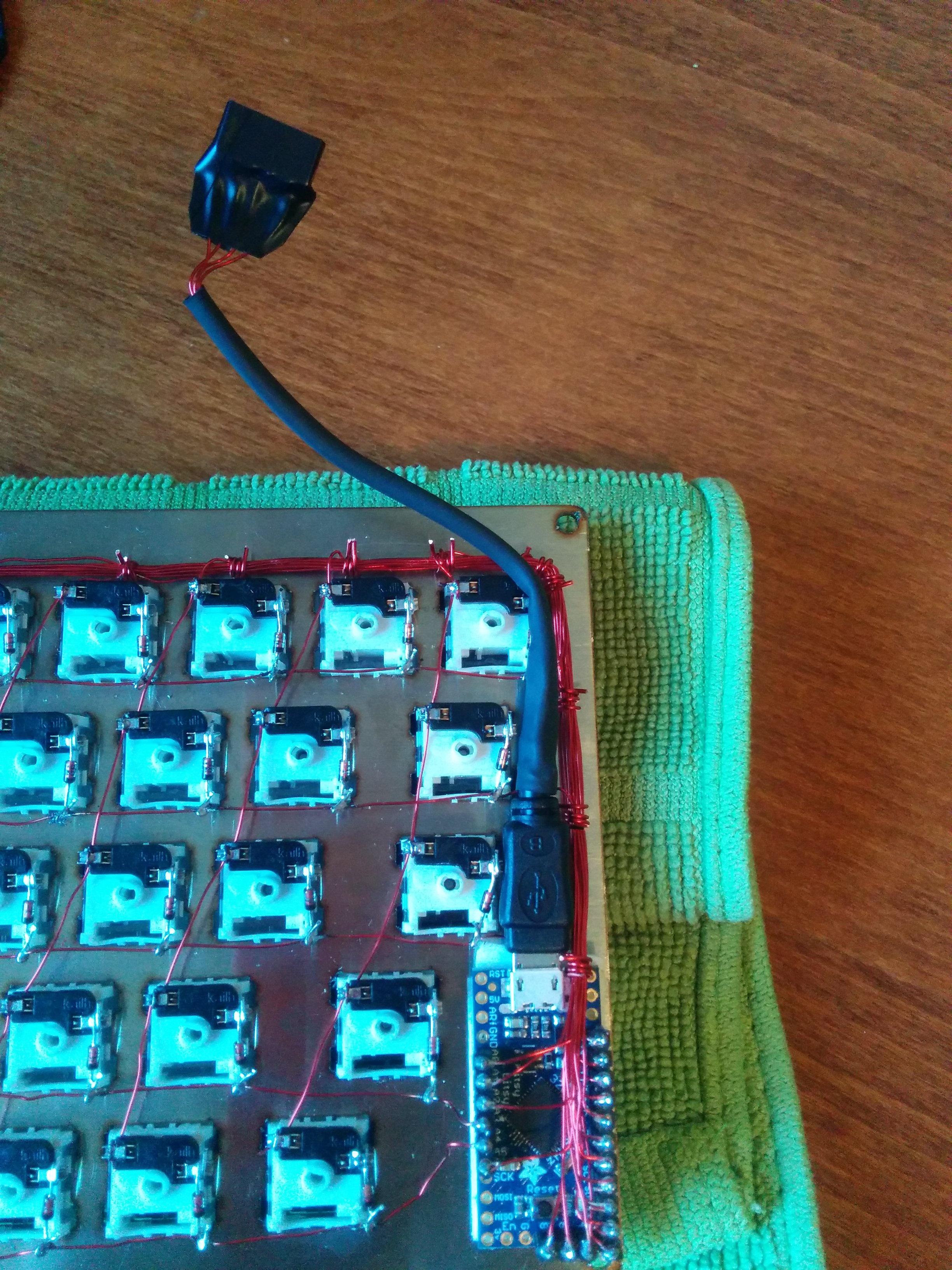

To do so, each row wire was laid across the (bent) lead of the diode. The diode lead was then folded to form a tight loop around the wire. I then soldered the wire to the lead using a hot soldering iron (which burnt away the enamel coating). Finally, I trimmed off the excess lead. You can see the final work product here:

Once the rows were completed, I then moved on to the columns. To assemble those joints, starting from the top of the column and working down, I wrapped the magnet wire around the socket lead tightly and then soldered to form the joint. The picture below show the completed matrix:

Of course, throughout the work, I tested the connection between the switch socket and the pin on the controller (though I must’ve missed one or something, as later I did discover a single bad diode on the control key that had to be replaced)!

It was here that I discovered an unexpected problem: the use of the sockets on the controller board resulted in the combined height of the controller, sockets, pins, and wiring to exceed the 10mm space I’d planned for the interior of the case.

I couldn’t complete assembly of my keyboard!

As a result, I had to put in an order for 15mm standoffs that would provide the space I needed, a mistake that lead to the one week delay in the assembly of the project…

Session 3b: Firmware

The interactive keyboard firmware designer provided me with a base firmware image I could work with, but not trusting the recency of the code it used, I chose to clone the QMK repository, copy over the layout to the QMK codebase, and build from an up-to-date tree.

I then applied a few tweaks and customizations to the firmware, altering the function layer a bit, switching the ESC key to a GESC hyper key, and so forth. Then I built the image and I was ready to write the firmware!

The only difficulty was in the flashing itself.

The QMK build instructs the user to connect the controller to the PC, then reset the board to load the bootloader, after which flashing progresses using avrdude.

However, I immediately encountered errors indicating that avrdude couldn’t talk to the controller (timeout errors of some kind).

After furiously scouring the internet for a solution to the error messages I was seeing I thought I might have been at an impasse, which would have been enormously disappointing. I spent so much time on this project already!1

Fortunately, I then decided to, you know, read the documentation, and the answer immediately presented itself.

It turns out that the Itsy Bitsy reset button must be pressed twice to enter the bootloader, and not just once.

Doh!

Once I followed the documented instructions, the flash proceeded successfully, and I pressed my first key. The letter ‘I’. And there, on the terminal, I saw it:

lappy:~$ i

Then, for kicks, I checked syslog:

usb 1-2: new full-speed USB device number 25 using xhci_hcd

usb 1-2: New USB device found, idVendor=feed, idProduct=6060

usb 1-2: New USB device strings: Mfr=1, Product=2, SerialNumber=3

usb 1-2: Product: keyboard

usb 1-2: Manufacturer: thebark

usb 1-2: SerialNumber: 0

input: thebark keyboard as ...

Mind blown!

I then tested the rest of the keys. And it worked! It all worked.

I have to honestly admit I was completed astonished. The fact is, as a programmer, the idea of something working the first time is utterly unheard of. Every programmer has experienced the feeling of code functioning on the first try and immediately furiously debugging to find that hidden error that must exist. It’s incredibly unnerving!

Now, given the amount of testing I performed along the way, I suppose I shouldn’t be totally surprised.

But I am certainly surprised a little!

Edit: And if you’re looking for the firmware for this project, check out my fork of the QMK repository on Github.

Session 4: USB breakout board and cable

While waiting for the new standoffs to arrive, I decided to assemble the USB breakout board and cable, and attach the foam to the bottom plate of the case.

To once again avoid soldering wires directly to pins, I attached a right angle pin header to the breakout board. I then built a custom cable, which would attach the USB port on the controller to the breakout board by cannibalizing a micro USB cable and wiring it to a compatible pin socket.

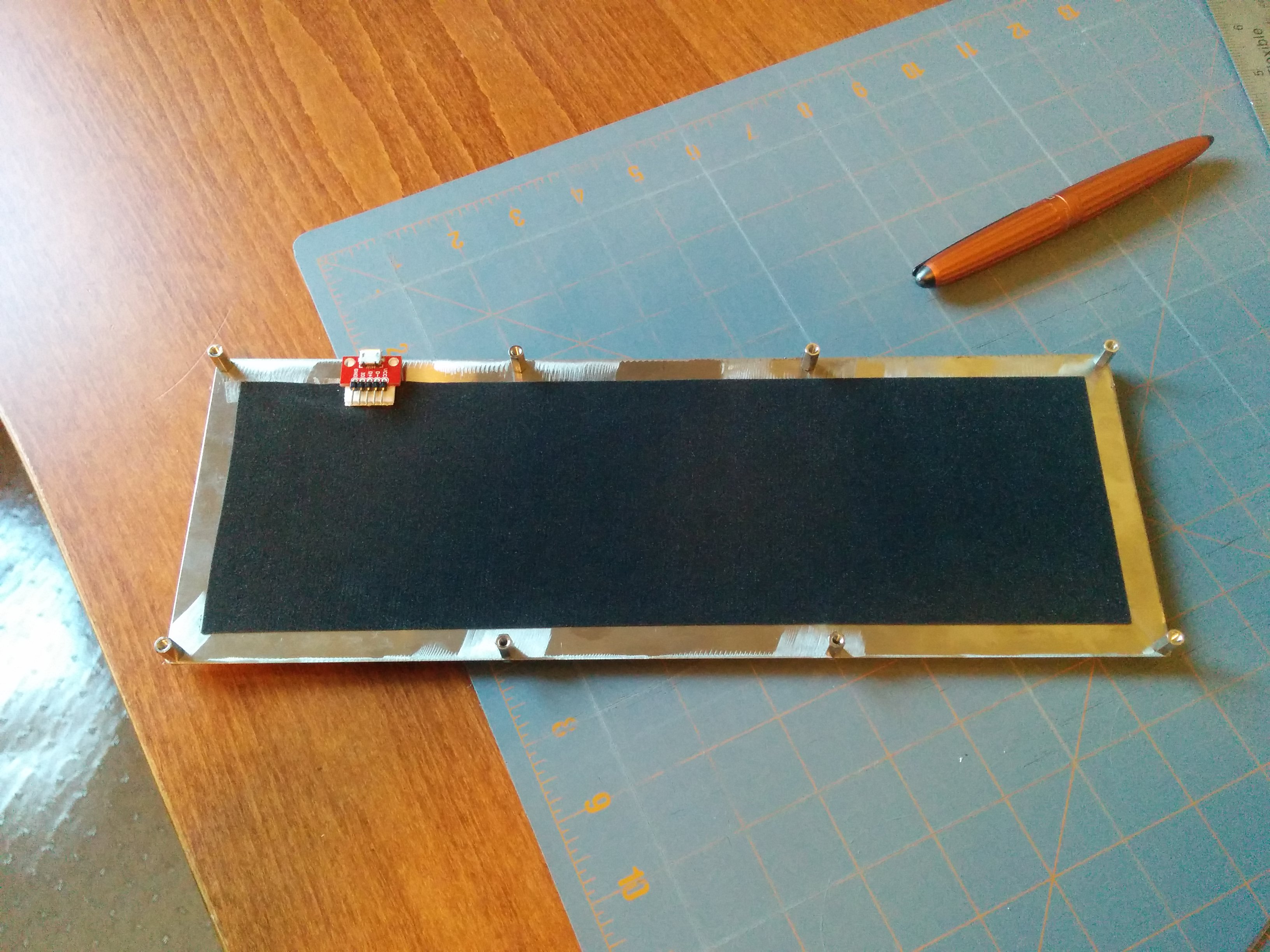

At this time I also cut the liner foam to fit the case, including a small cutout where the USB breakout board would be mounted, and attached it to the case using double-sided tape.

And how did I mount the breakout board?

You guessed it: 3M Control adhesive strips! What can’t they do?

You can see the breakout board and back plate here:

And here, you can see the custom cable attached to the controller:

Obviously, throughout this work, I tested each connection and performed a final test by connecting the keyboard to my laptop through the breakout board. Yup, that also worked perfectly!

Session 5: Final assembly

Due to the wait for the standoffs, plus an intervening work trip, it wasn’t until the following Friday that I was able to complete final assembly of the keyboard.

First, I needed to attach the keyboard feet to the bottom of the backing plate.

Yes, once again, I used those 3M strips! Now, I must admit, it was here that I made a bit of a mistake. I ordered some new strips from Digikey, thinking I was picking up the adhesive velcro versions, only to discover that, no, I only picked up the double-sided adhesive versions.

Oh well! They still work, even if the setup isn’t as adjustable as I’d like.

You can see the feet mounted to the case in the picture below:

With the feet attached, I could take the final step: assembling the case with the new, 15mm standoffs I’d acquired.

And here it is, the final product!

-

In hindsight, I should’ve tested flashing the firmware to the Itsy Bitsy before ever proceeding with the build to ensure no surprises at this stage in the project. ↩

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{{ webmention.content }}

{% endfor %}

No bookmarks were found.

{% endif %}Likes

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{% if webmention.author %} {% endif %}

{% endfor %}

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{{ webmention.content }}

{% endfor %}

No links were found.

{% endif %}Replies

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{% if webmention.author %} {% endif %} {% if webmention.content %} {{ webmention.content }} {% else %} {{ webmention.title }} {% endif %}

{% endfor %}

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

- {% endfor %}

-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

- {% endfor %}

No reposts were found.

{% endif %}-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

- {% endfor %}

No RSVPs were found.

{% endif %}-

{% for webmention in webmentions %}

-

{% if webmention.author %} {% endif %} {% if webmention.content %} {{ webmention.content }} {% else %} {{ webmention.title }} {% endif %}

{% endfor %}

No webmentions were found.

{% endif %}